Leslie Arthur Wilcox - British Marine Artist

By Malcolm Lambe

Before Leslie Arthur Wilcox was known for painting ships and yachts, he was already earning a living as a commercial artist. He left school at fourteen. Around the same time, a watercolour of an aircraft won him an art competition in a national newspaper and led directly to his first job, in an advertising studio in the Strand, in London. It was there that he more than likely learned his trade: clarity, speed, and how to make an image work from across a room rather than up close.

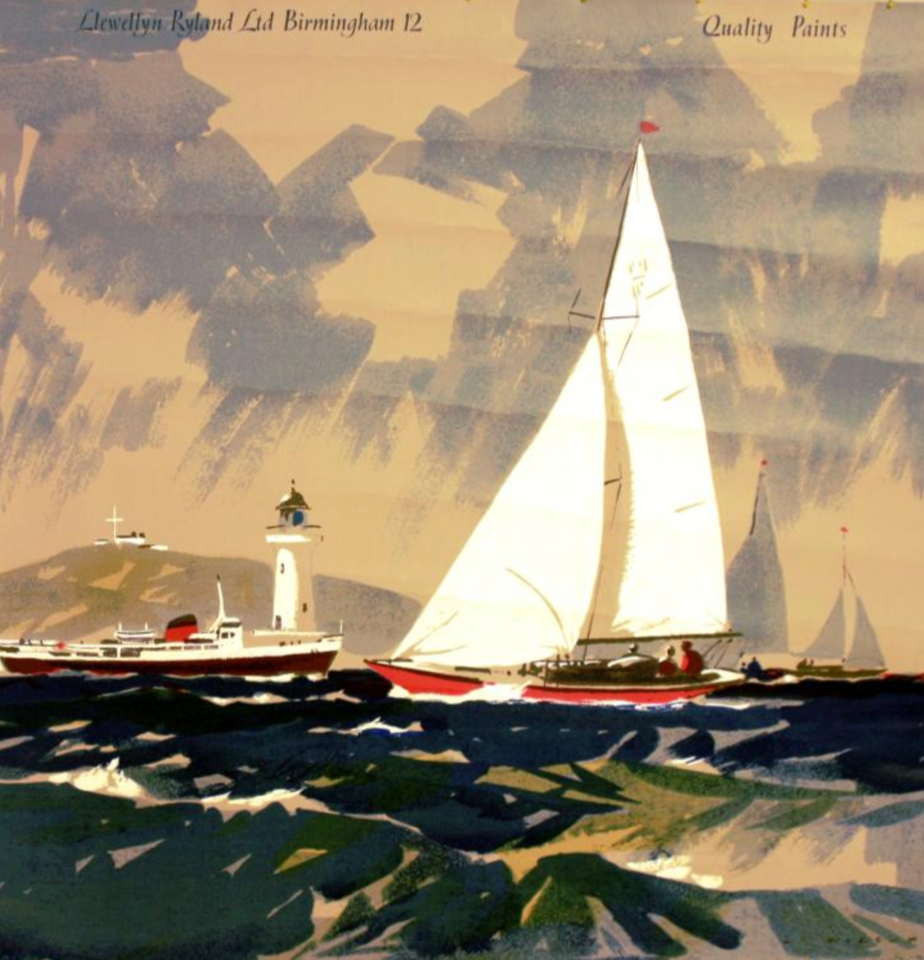

That background carried through his inter-war poster work. Wilcox produced a number of travel and marine-related posters in the 1930s and 40s, including designs for maritime coatings and coastal travel. They are economical pieces of design - strong silhouettes, limited colour, and an immediate sense of scale and movement. Boats are shown as working objects, not ornaments, and the sea is treated as something with weight and texture rather than decoration. (click to enlarge)

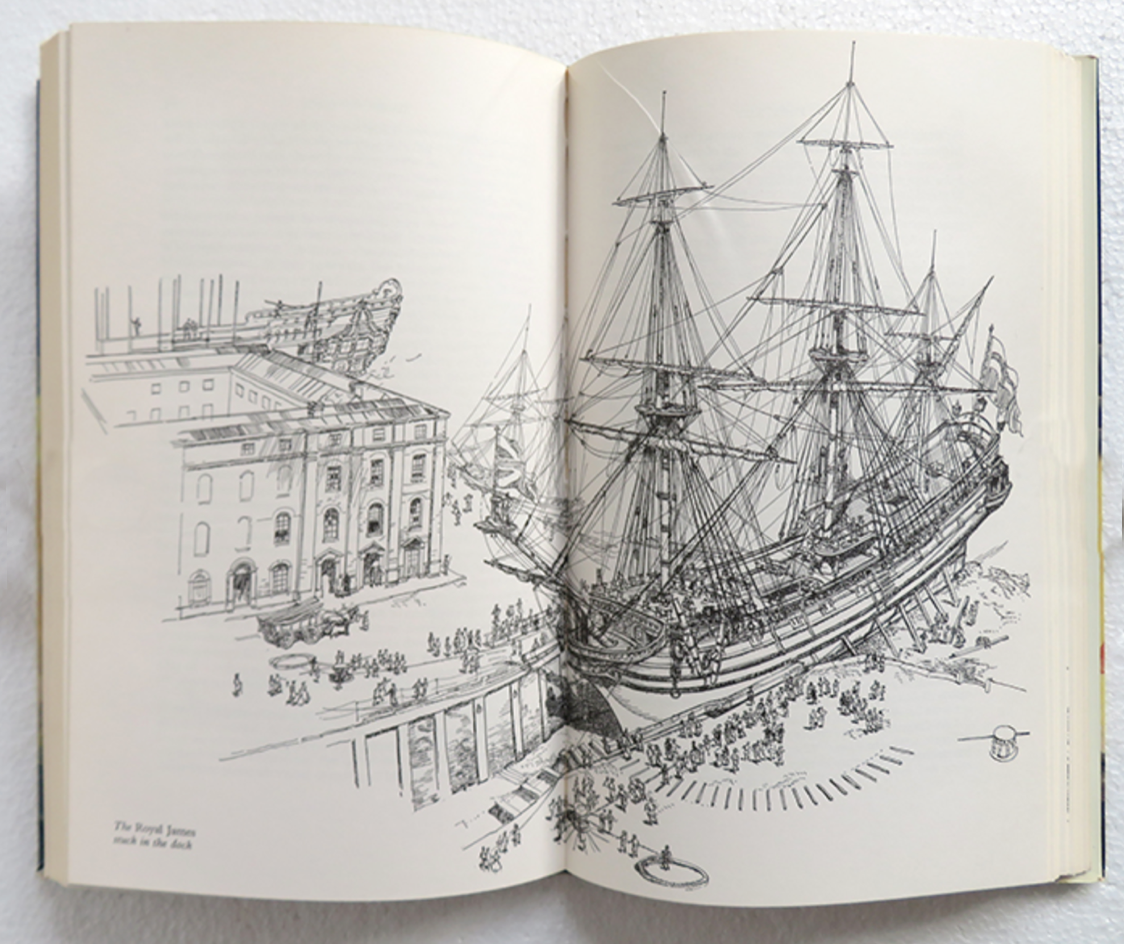

Wilcox also wrote and illustrated several books, most notably Mr Pepys’s Navy, a lively, visually dense account of the seventeenth-century fleet seen through Samuel Pepys’s eyes. It plays directly to his strengths: rigging, hulls, dockyards, half-models, the clutter and choreography of working wooden ships. The drawings are meticulous without being dry - informed by research, but clearly made by someone who enjoyed the subject rather than merely documenting it.

The book reinforces the sense that Wilcox was as interested in how wooden vessels were made, fitted and managed as in how they looked under sail.

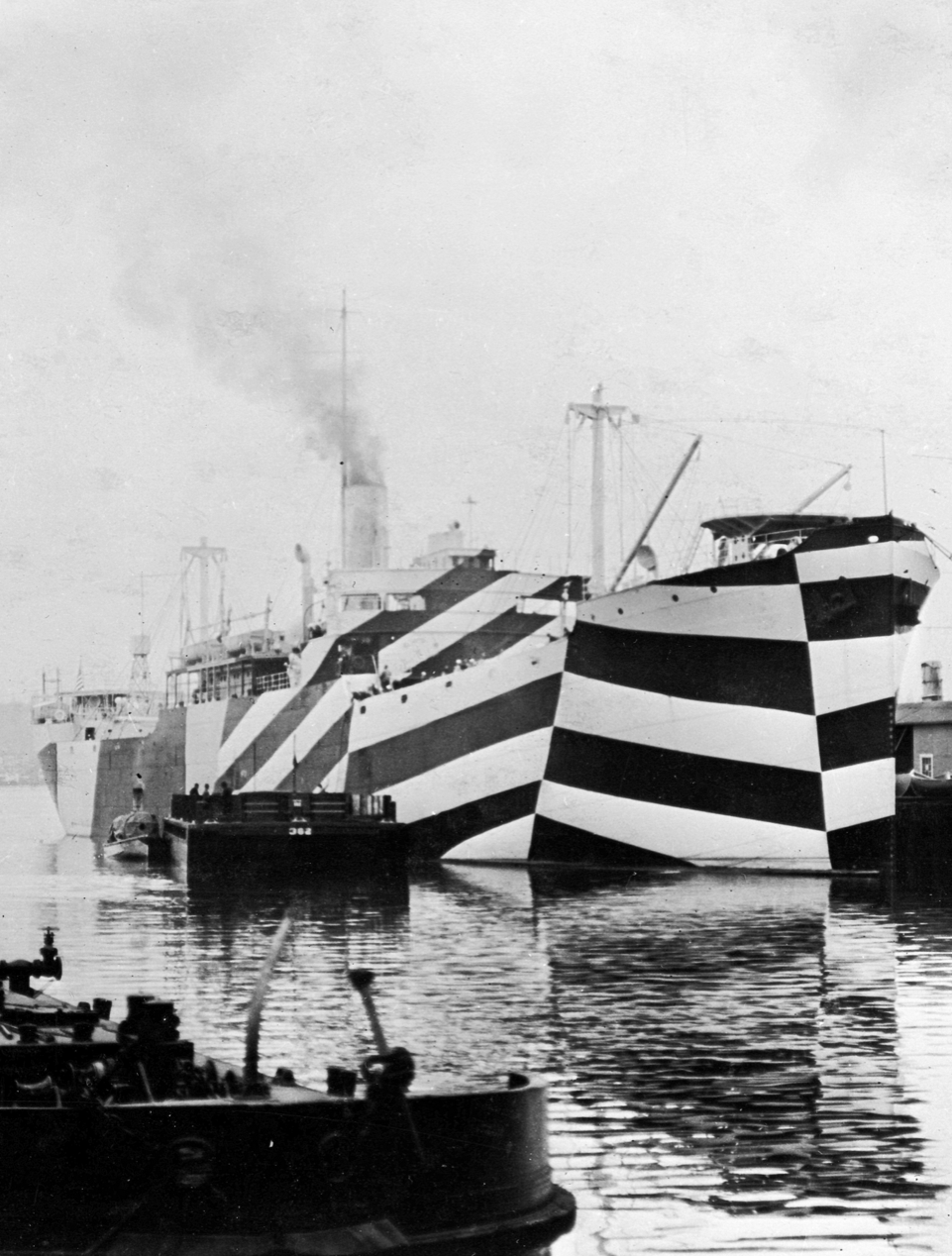

Those same instincts proved unexpectedly useful during the Second World War. Wilcox spent several years as a Royal Navy camouflage officer, not at sea but inland, attached to the Admiralty’s Naval Camouflage Unit at Leamington Spa. This was not camouflage in the jungle sense. Wilcox and a small group of artists and designers worked on scale ship models, painting and repainting them with disruptive patterns, then studying how they appeared under different lighting and background conditions. The aim was not invisibility but misreading - making a ship’s size, heading and speed harder to judge through a periscope.

One of the artists working alongside Wilcox was Colin Moss, who later described Leamington Spa as a workshop rather than an office: models on turntables, artists in overalls, and paint everywhere. It was an unusual war job for painters, but a practical one. These were people who understood hulls as shapes with consequences.

An impression of the Leamington Spa workshop by Anne Newland 1913-1997

Workers sewing and designing camouflage in the workshop at Leamington Spa by E. La Dell

When Wilcox returned to civilian life, that way of seeing remained. His post-war paintings of clippers, naval vessels and yachts show a consistent concern with how a hull sits in the water, how weight is carried, and how a vessel reads at distance. Details are restrained; proportion and balance do most of the work.

That is where Wilcox’s work leaves you with more questions than answers. For all the clarity of his paintings and posters, the man himself remains oddly elusive. There is surprisingly little personal material to go on. No memoir. Few anecdotes. No easy sense of how he lived when he wasn’t working. Did he own a boat? Did he enjoy sailing, or was the sea something he mostly observed from shore and dockside? What did he drive? A person’s car often tells you something about them, but even that detail seems to have slipped away. I find myself imagining him behind the wheel of something British - a pre-select gearbox Lanchester perhaps - but it’s only conjecture. Like much else about Wilcox, the man remains just out of focus.

There are occasional glimpses of Wilcox’s private life, though they are mostly indirect. His son, Ingram Wilcox, who is also an illustrator, went on to become a well-known figure in British quiz culture, winning the £1,000,000 prize on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” and appearing on programmes such as Mastermind, Brain of Britain and Fifteen to One.

What survives instead is the work of Leslie Arthur Wilcox - carefully composed, often nostalgic by design, and clearly shaped by someone who spent years thinking about how boats are seen, remembered and understood. In that sense, Wilcox feels less like a personality-driven artist and more like a craftsman who left the pictures behind and quietly stepped out of frame

I wish I’d known the man. Youngest of five children from a working-class family in Fulham. A self-taught artist who rose to become Honorary Secretary of the Royal Society of Marine Artists and a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. His work is held in collections around the world, including the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and the Royal Collection.

In 1954, Wilcox was commissioned by the National Maritime Museum to paint “Arrival of the steamship Gothic at Sydney”, depicting the arrival of HM The Queen and Prince Philip during their post-Coronation Commonwealth tour. The scene shows Sydney Harbour crowded with small craft, flags and spectators, the liner riding high amid the chaos. The vessel Gothic, was a working Shaw Savill & Albion liner pressed into royal service while Britannia was still being commissioned.

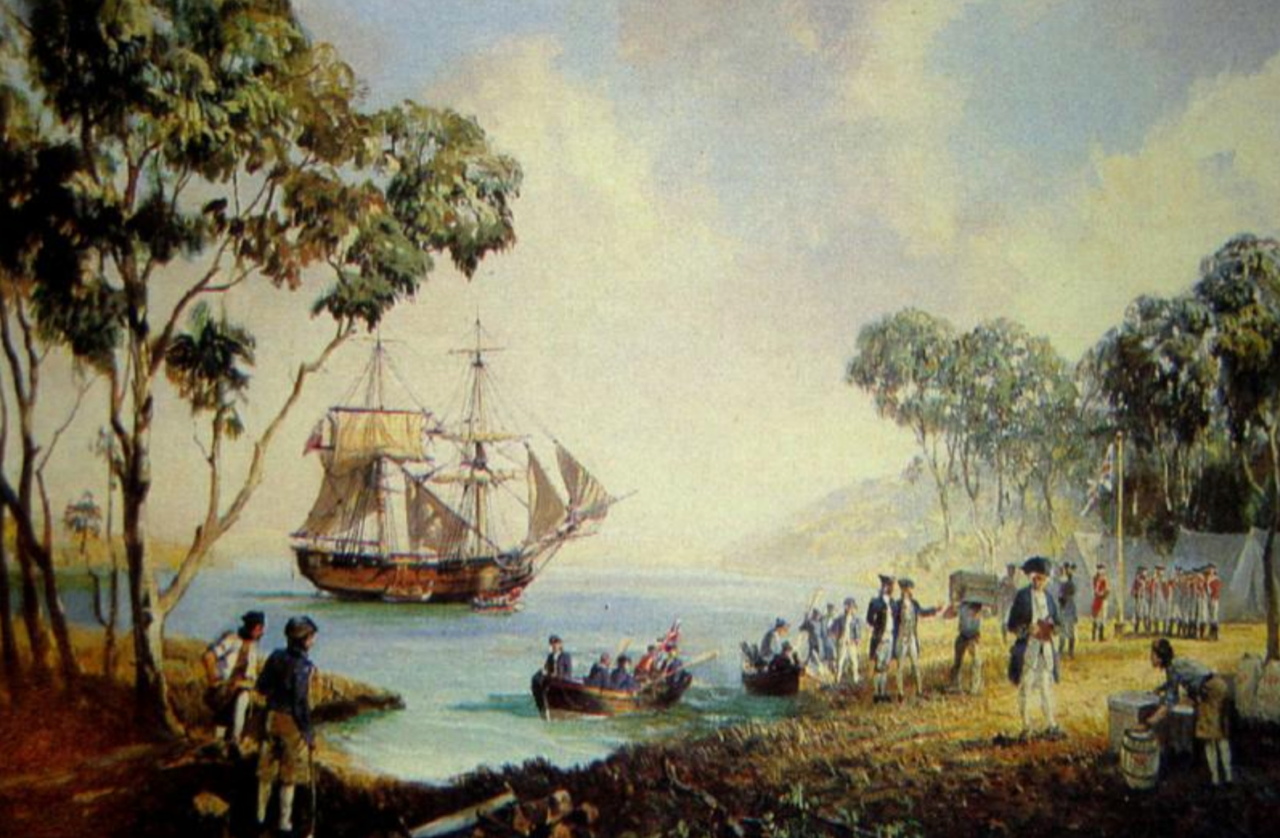

L A Wilcox paintings and prints appear in the Australian Art Sales Digest - including a rather cheesy rendering of Sydney Cove, 26 January 1788 - showing Captain Arthur Phillip raising the flag and declaring “Me hearties...this is the finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand ship of the line may ride in the most perfect security… and mark my words…future generations will commemorate this day with a nationwide piss-up”.

Postscript: I wonder if it was a Lanchester? I don’t see him in a Bentley. Maybe a Morris Minor Traveller - the wood-framed estate car. Yeah I reckon that’s what he would have driven. Enough room in the back for easel, paints and the Cocker Spaniel.