Now Fallen Into The Public Domain

One of our favourite discoveries this year has been the website The Public Domain Review.

Many of its values and goals express what we are trying to do here at SWS, but in a broader sphere of art, literature and ideas.

Perhaps its best expressed in their own words.

Founded in 2011, The Public Domain Review is an online journal and not-for-profit project dedicated to the exploration of curious and compelling works from the history of art, literature, and ideas.

As our name suggests, the focus is on works now fallen into the public domain, that vast commons of out-of-copyright material that everyone is free to enjoy, share, and build upon without restriction. Our aim is to promote and celebrate the public domain in all its abundance and diversity, and help our readers explore its rich terrain – like a small exhibition gallery at the entrance to an immense network of archives and storage rooms that lie beyond.

With a focus on the surprising, the strange, and the beautiful, we hope to provide an ever-growing cabinet of curiosities for the digital age, a kind of hyperlinked Wunderkammer – an archive of content which truly celebrates the breadth and diversity of our shared cultural commons and the minds that have made it.

Here are a trio of maritime related stories to help whet your appetite

Remembering Scott

By Max Jones

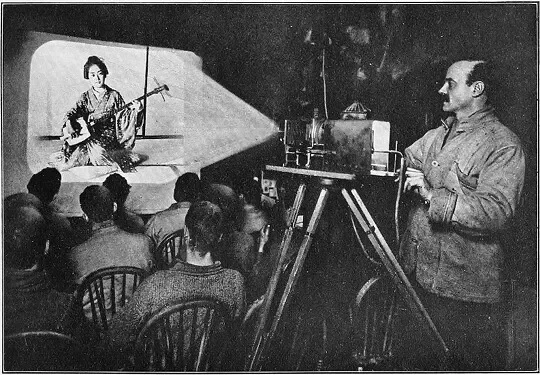

The photographer Herbert Ponting giving a lecture on his travels in Japan to the Terra Nova team in the hut at Cape Evans.

Why are some historical figures remembered, while others are forgotten? Major-General Henry Havelock was the toast of the nation in 1857. One of the British heroes of the ‘Indian Mutiny’, Havelock died after the relief of the city of Lucknow. Such was the fame of the devout Christian soldier, parliament approved the erection of his statue in Trafalgar Square, which still stands today. A decade ago, however, Mayor Ken Livingstone complained that most Londoners had no idea who Havelock was.

The memory of Captain Scott, who died in Antarctica one hundred years ago, has fared much better than Havelock’s. The centenary of Scott’s last expedition has generated a wave of books, events, radio broadcasts and television documentaries over the last two years, including BBC 2’s The Secrets of Scott’s Hut fronted by modern celebrity-explorer Ben Fogle, a major new exhibition at the Natural History Museum, and a national memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Scott’s exploits in the uninhabited continent of Antarctica are free of the troubling associations which surround many other imperial heroes. Should the statue of a man known primarily for subjugating India still stand in the centre of a city where over one in ten of the inhabitants have roots in South Asia? As with so many aspects of our imperial past, Britons have found it easier to ignore and forget rather than confront such difficult questions.

In part, of course, Scott is remembered today because his last expedition is such a great story: the drama of the race with Norwegian Roald Amundsen; the heart-breaking arrival at the South Pole a month too late; the agonising suspense of the return march; the tragic end only 11 miles from a supply depot which would have saved them. Yet a great story alone offers no guarantee of remembrance. Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition and his incredible boat journey to South Georgia were surprisingly neglected in Britain until the end of the 1990s.

John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1778) by Melissa McCarthy and Hunter Dukes

It’s too late to save the leg, which has been bitten off below the knee. But Brook Watson, the floating blonde youth depicted in Copley’s oil painting, will be rescued from the jaws of this tiger shark and go on to enjoy a long life as a London merchant, becoming Lord Mayor in 1796 and a baronet in 1803. His rise bred envy: “in spite of his later elevation”, wrote one of Copley’s detractors, “there are those whose sympathy is with the shark”.

Though based on true events, we view this work from the distant vantage of its artist’s imagination: Copley had never visited Cuba, the backdrop of his fearful tableau. Born in Boston in 1738, he enjoyed a successful career as a portraitist — with sitters including the likes of Paul Revere and Samuel Adams — gaining international fame for a study of his half-brother Henry Pelham, A Boy with a Flying Squirrel. Although Copley’s sitters and social circle included people from both sides of the political divide, as tensions mounted in the years leading up to the Declaration of Independence, the artist found himself liable through marriage. His father-in law, Richard Clarke, was one of the Tory merchants whose product had been destroyed during the Boston Tea Party. When a group of independence-seeking Whigs threatened Copley, he set off abroad.

Six and a Half Magic Hours (1958)

6 1/2 Magic Hours is a Pan Am promotional film marketing transatlantic air travel at the dawn of the jet age. While at heart an advert for their "magical" service of a flight from New York to London in only 6.5 hours, we are also treated to a nice summary of jet travel history up to that point, the pinnacle of which was their Flight 1000. Thanks to the new jet planes, the public could travel in a faster and easier way as they enjoy the "attractively decorated" and air conditioned plane as well as the "gourmet" meal which bears no resemblance to the boxed meals we are now used to. The interior of the plane is also rather luxurious, with spacious powder rooms for the ladies and a lounge-like area where people can read, play games or have drinks, all whilst being offered a platter of hors d'oeuvres. The silky-toned voice-over declares that "travail has been taken out of travel" and that "Jet speeds will help to accomplish one of man's long-sought goals: an easy interchange of peoples throughout the world".

Keeping an eye on works that are passing into the public domaine is fun but its also vitally important because culture is cumulative not static. New work is always a derivation of came before it, whether through adaptation, reinterpretation even parody.

And copyright was always intended to be a temporary incentive, not a permanent protection. Once that limited period has done its job, works should become part of the shared intellectual and cultural inheritance of society. Thank you to the The Public Domain Review for making this process so enjoyable.