The Pure Poetry of the shipping forecast

By Jo Ellison at the Financial Times

It’s always seemed one of the more yawning ironies that a nightly radio dispatch designed to protect sailors from the most treacherous stretches of water should have been co-opted by half of its audience as being the equivalent of aural Xanax.

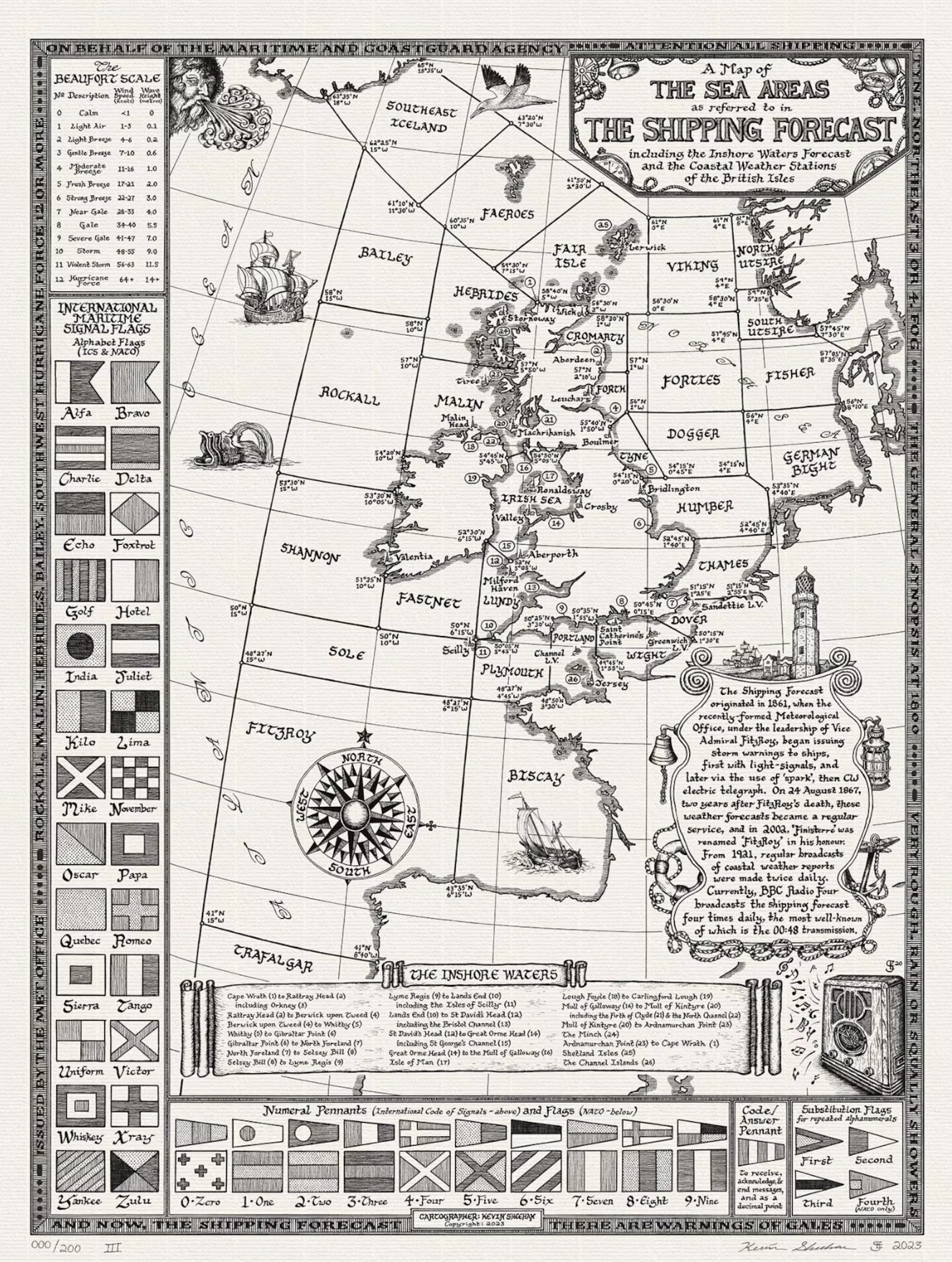

The shipping forecast celebrates its centenary this week. Or, at least, the Maritime and Coastguard Agency is marking the 100th anniversary of its first broadcast. Conceived in 1861 by Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy, according to a government press release, the maritime weather warning was developed following the loss of the steam clipper Royal Charter, which sank off the coast of Anglesey in 1859 with the loss of 450 lives. Produced by the Met Office on behalf of the MCA, a version of the weather bulletin began in 1924, although it was only broadcast by the BBC in 1925.

In the course of its existence, the forecast has saved thousands of lives but its practical application has long been superseded by more precise meteorological and satellite data: the forecast is said to be around 93 per cent accurate. Hence, the vast majority of its remaining 6.5mn listeners today are landlubbers, tucked up safe on dry land.

Over time it has become a beloved cultural icon, a tacit expression of our national identity, and although the bulletin is broadcast four times daily, it is the 00.48 edition that has become a nightly liturgy. Poised somewhere between the highest finger beam of moonlight and before the birds start squawking, the forecast is a fixed point for insomniacs, easing the anxious souls into a more somnambulant world.

As an exercise in creative writing, the forecast is pure poetry: odd, that a project of hard science should now have been enshrined as art. Its exotic roll call has been eulogised by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney — “Dogger, Rockall, Malin, Irish Sea:/Green, swift upsurges, north Atlantic flux/Conjured by that strong gale-warning voice,/Collapse into a sibilant penumbra” — while its natural lyricism has been exploited by everyone from Radiohead to Blur.

It’s the place names in the forecast wherein the real emotions stir. Like something out of Dickens, we imagine fragments of each place: the barren Rockall, Scottish Cromarty, swagged in tartan, enticing Biscay, German Bight. The very strangeness and old-timey romance of each station conjures a world before Google maps. As is noted in Sanna Nyqvist’s essay “Poetics of the Shipping Forecast”, the science of cartography is also a means by which to navigate and reflect upon ourselves. Like examining the Milky Way, listening to the forecast reassures us of a certain permanence in a strange and changing world.

My affinity with the forecast developed as a one-time member of the maritime community, inasmuch as I once “sailed” the waters of Chelsea while living on a houseboat on the Thames. Our mooring was hitched to one of the city’s most prestigious postcodes: I stepped off the boat and on to Cheyne Walk, a street whose massive mansions were owned or formerly inhabited by such luminaries as Mick Jagger, Ian Fleming, Paloma Picasso and George Best.

The River Thames at Cheyne Walk

Our boat was permanently moored there on account of its being about to sink: it leaned heavily to the starboard, and I had to rig up a plastic chute around the bed to catch the unnervingly treacle-coloured leaks. In winter it was a little less well insulated than a cardboard box and the electric wiring around the hull was worryingly exposed. We were eventually evicted because the boat was rightfully condemned.

Even so, for some nine months in my early twenties I considered myself the very height of chic: I could nip into Partridges, the poshest Chelsea grocer, to buy my dinner, and my rent was only £90 a month. During that time I also developed a keen awareness for the vicissitudes of water: far from lulling me to sleep at night, the Thames would slap the wall next to my head. High tide at night time became a point of terror as the boat would rock with unprecedented violence. I would marvel that even in the centre of London, one was still completely at the mercy of a greater and more powerful natural force.

At night, listening to the Thames hiss and gurgle on the shoreline, I would wait for the calm of “Sailing By”, the strange little maritime waltz composed by Ronald Binge that would preface the night’s forecast. And while I could never understand a word of the forecast, and all the weather conditions seemed “moderately poor”, I found great comfort in thinking of other people lying in their boat bunks being lurched around with me. Turns out, I wasn’t very shipshape. The boat was freezing and damp. For years after, I had a recurring nightmare that I was drowning, and have never willingly slept on a boat again. Tyne and Dogger, on the other hand, have become my fondest friends. And that sweet, melodious shipping forecast will always be my favourite lullaby.

POSTSCRIPT

The forecast is given in Beaufort Wind Scale. While we mostly use knots, the calibration of FORCE has almost become a literary one with so many stories and books like Fastnet Force 10. The scale was developed in early 19C by Royal Navy officer and hydrographer Francis Beaufort. It was officially adopted in 1830 and first used by HMS Beagle under Captain Robert FitzRoy circumnavigating from 1831 with Charles Darwin on board. FitzRoy's contribution has been honoured with sea area 19 Finisterre being renamed after him. That sees-off the ole'enemy.