The Lateen Sail

Regular readers will have noticed the soft spot that your editor has for the craft of the western Indian Ocean so we were fascinated to see Duncan Blair’s latest article. Following the two recent articles on the Gaff Rig DUNCAN BLAIR continues with his personal history and assessment of different rigs with an explanation of the Lateen Sail.

The Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea and Beyond.

(This post is Part One of a two part piece on the Lateen Sail. )

It is deceptively easy to get bogged down in the dominant paradigm of Traditional Sail that is centered on the archaeology and history of square rigged ships and fore and aft rigged work boats. This is, admittedly, a broad generalization, but it is also one that I would defend.

I will do my best to describe and present images and analysis of the Lateen rig, as I understand it. I will also use maps to illustrate the the vast scope of the trade routes based on the seasonal monsoon winds and the lateen sails that used them.

I will also give examples and comments on the types of cargo that were carried for centuries using the sailing technology of the Arab dhows sailed by generations of Arab, African and Indian seamen.

It was these sea routes, used for trade coming from Africa, India, the East Undies and even China, that the Portuguese and the Dutch would eventually “discover” and go on to control.

But this trade was not new, it was just hidden from Europe by distance, geography, inadequate sailing technology and deception.

The Age of Discovery changed all that, but it had not yet begun.

When it did begin, fueled by European blood and treasure, it had wisely included the technology of the Lateen rig.

A Portuguese caravel in The East Indies , known today as Indonesia. She has three masts rigged with lateen sails and a square rigged foremast. Artist; Hervey Garrett Smith.

ALAN VILLIERS

Alan Villiers (DSC, born 1903, Melbourne, Australia. Died 1982.)

Villiers has been described as a sailor, journalist, and author. For me he is best understood as a Master Mariner.

In the 1930s, before his service in World War Two, Villiers traveled extensively in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the East coast of Africa. During WW II he was in the Bay of Bengal, specifically Burma, now known as Myanmar.

As a writer he described his experiences in several of his books. Many of the photos presented in this blog came from Villiers’ book entitled Men,Ships and the Sea.

DHOWS

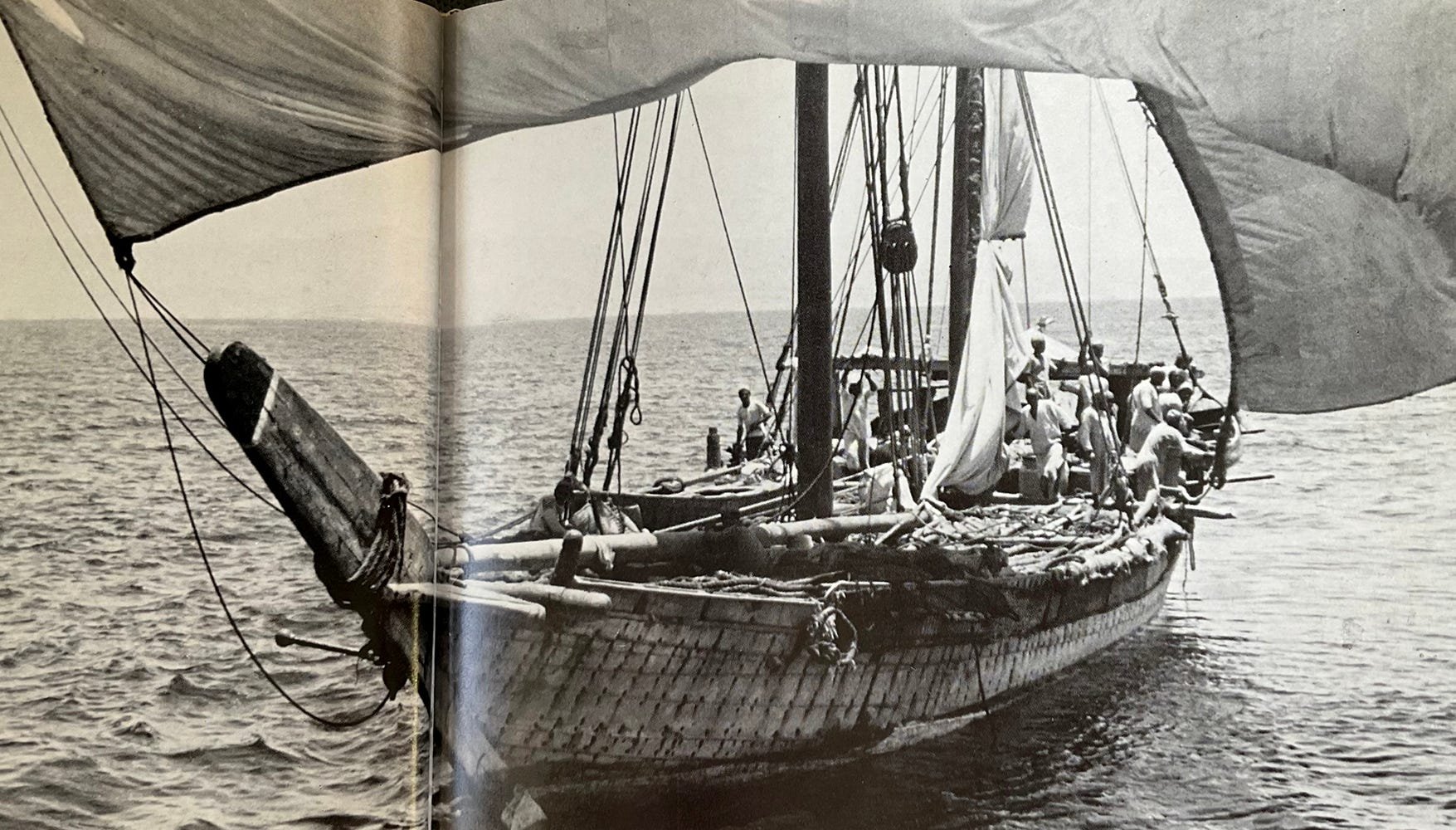

Arabian Dhow, (Sails Through the Centuries, 1965.).

Villiers wrote “The first thing I discovered was that Arabs know none of their vessels as Dhows. They are known by their hull forms; booms, bagalas etc. All of their rigs are much the same.”

I will use the general term”dhow”, as Villiers himself does, when referring to the various types of lateen rigged sailing vessels in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

THE LATEEN RIG

The traditional lateen rig is characterized by its large triangular sail and the long, curved yard that carries the sail.This yard, reflecting the arid environment of the sail’s origin which is devoid of tall trees, is made by using several separate spars, overlapping each other, then “fished” and lashed together, making the yard both strong and flexible.

Villiers comments, “The long lateen yard, cumbersome as it may appear to European eyes, is indeed the ideal means of setting a big running or reaching sail, and the dhows of the Indian Ocean had the qualities of yachts for centuries before yachts were even thought of.”

(The Monsoon Sea, pg. 57)

One of the Indian Ocean dhows that Villiers sailed on was of a type called a “boom”. Her yard, made of wooden poles fished and lashed together, was “tremendously strong” and at 105 feet long it was the same length as the hull of the “boom”.

BAYAN, the “boom” that Villiers lived on while sailing in the Indian Ocean. As stated above, her 105 foot long main yard was equal in length to her hull.

Villiers comments that the hull capacity of dhows was not measured in tons, but in the number of 180 pound date baskets of a standard size that they could carry.

To me this allows an interesting cross-cultural comparison with other standard units of cargo capacity.

Some examples are; European barrels of 60-80 gallons, modern container ship TEUs (8 feet by 20 feet) steel shipping containers, the Hanseatic League”load” of 2 tons per wagon, and the Gulf of Mexico oyster fishery standard unit of a burlap bag filled with 60 pounds of oysters.

The boom BAYAN held 2300 date baskets, each weighing 180 pounds. 2300X180 = 414,000 pounds, equal to 207 tons—all of it powered by sail.

RIGGING

On the topic of rigging, Villiers comments that “The few stays used to support the mast when sails were set were lengths of Coir rope set up with tackles and these were shifted every time the sail was trimmed.”

Two crewmen on the foredeck of BAYAN with hawsers. Photo by Alan Villiers.

The hawsers shown in the photo are made of Coir, the fiber coming from coconut husks. Take time to look closely at this photograph.

The Coir hawsers appear to be 3 strand, cable laid.

On both hawsers the lower ends transition from being cable laid to being braided—something many of us still do, almost 100 years later, braiding the partially unlaid strands of cordage that is still useful, so as to be able to continue to use it in some way.

Each of the crewmen has his right hand on a section of the hawser that is served, just above the braided section, covering the transition from laid to braided. And in both cases the service also shows a spiral, in a simple pattern I know as a French Spiral.

THE HULL

“The Arab, left to himself, cannot build an unsightly vessel.” Alan Villiers.

Villiers goes on to explain that most dhows, at least those in the 1930s, were strongly built with teak lumber coming from the Malabar Coast of India; the West coast of India, from Calicut—now Calcutta—South to the southern most point of the sub-continent.

Not having conifer forests to provide Naval Stores, like pine tar, rosin, pitch and turpentine, the dhow captains hauled their boats once each year in order to apply a layer of fat, mixed with lime, onto the hulls, below the water line, as protection against teredo worms.

The fat came from camels, presumably butchered for human consumption and the lime, presumably, came from limestone or coral burned in a simple kiln.This process is also used in many other cultures to make lime used in masonry mortar.

THE SAIL

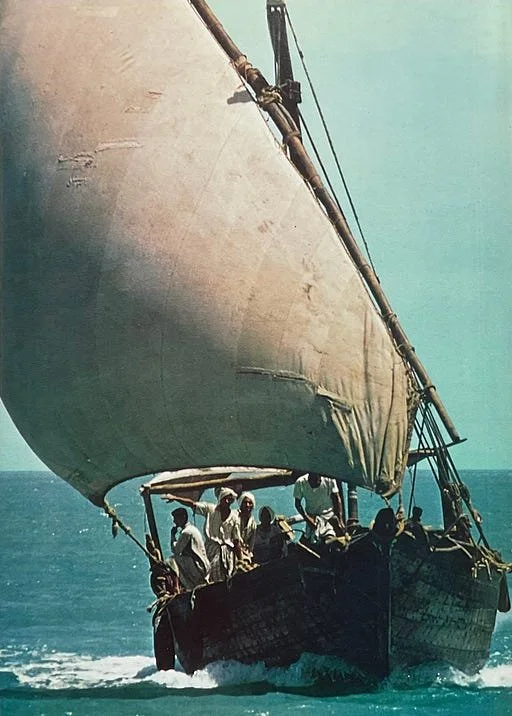

A Kuwait fishing dhow. Note the repairs on the sail above the tack. Indian Ocean dhows had sails made from Egyptian cotton.

This is Villiers’ description of how a dhow goes from one tack to the opposite tack.

“To change tack, a dhow wears ship—swings its stern into the wind (i.e. gybes). The sheet is let go. The sailors haul the yard upright before the stumpy mast, shove the foot of the yard to the other side and retrieve the sheet. Each time the yard is shifted from one side of the mast to the other, rigging has to be taken down and set up again. Yet dhows maneuver with amazing speed.”

Today, almost 90 years since Villiers sailed the Indian Ocean, this all seems very clumsy, cumbersome and inefficient, and in some respects it is, until you begin to consider the circumstances that underlie it.

This is the way things were done for centuries, so if it ain’t broke don’t fix it.

The crewmen were not paid a wage; they got food, water and a narrow piece of deck to sleep on. There were many crew men, but they were “employed”, sort of, and they were working and not wards of the state. Because of their religion they were also allowed to face Mecca and offer prayers 5 times every day, something that would never have been allowed on a European merchant vessel.

Each crew man was also allowed to bring aboard a personal chest of trade goods that he could barter, for profit, in the many ports where the dhows stopped.

Traditional Sail in the Western World, predominately non-Islamic, also relied on clumsy, often inefficient and poorly paid human muscle power. Halyard winches and sheet winches are relatively recent. Hauling braces and sheets and straining to raise large anchors by walking, barefoot, around a capstan were all commonplace forms of effort.

So sail trimming and other jobs on the dhows can be understood, in retrospect, as being culturally and socially appropriate—from the perspective of an Islamic culture base on hierarchal rules and traditions

Finally, like it or not, the advantages of the lateen rig, even from today’s perspective, far exceeded its disadvantages, especially given the available supply of cheap labor.

[Part Two of The Lateen Rig will be postedlater this year and will focus on trade routes, the importance of the monsoon winds to the Indian Ocean-East Africa trade and the types of trade goods carried by the dhows.]

PAU

Duncan Blair

REFERENCES

Men, Ships and the Sea, Alan Villiers, National Geographic Book Service, 1973.

Monsoon Seas, Alan Villiers, McGraw Hill, 1952.

Sails Through the Centuries, Sam Svensson, The Macmillan Co. 1965.

Duncan Blair’s Traditional Sail Website can be found HERE