Booms, Baggalas and a boy from Essendon

A book review of “Sons of Sinbad” by Alan Villiers

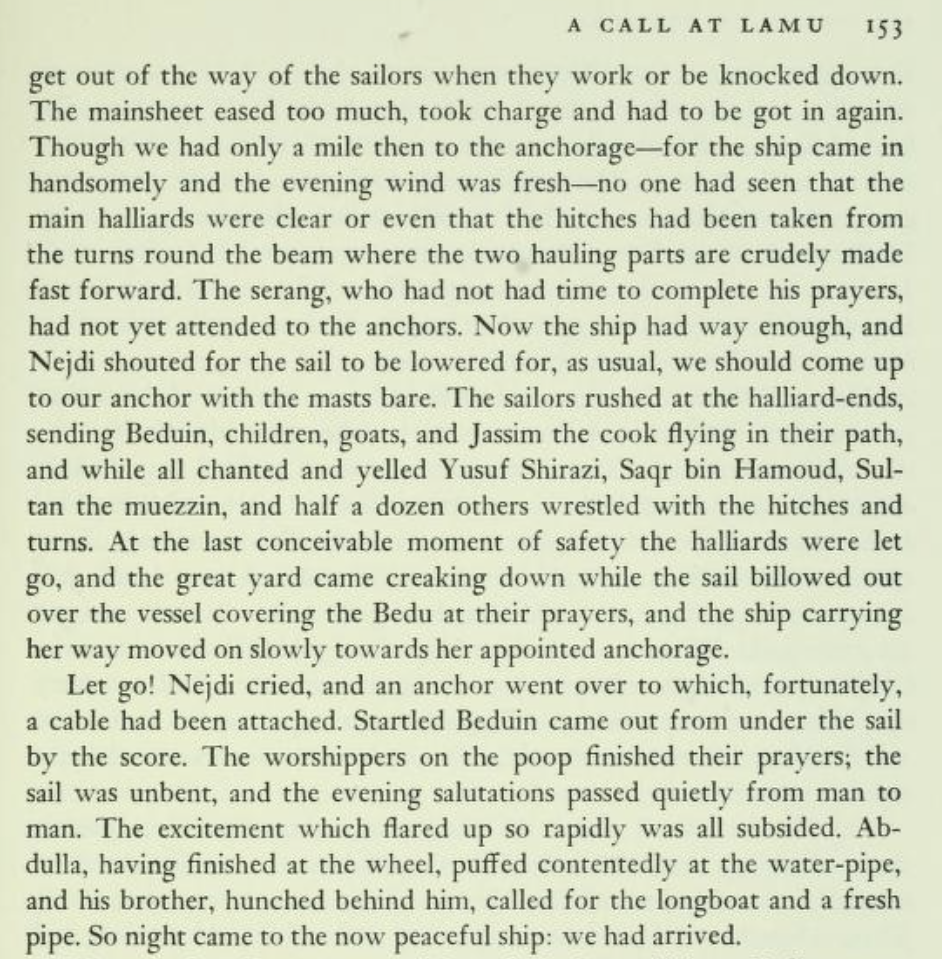

Sailors climbing the halyard blocks on the Triumph of Righteousness © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

When you think of the great maritime writers whose stories draw on years of experience standing on a timber deck, rather than sitting in a comfortable armchair, names like Moitessier, Slocum, Hemingway and Conrad come to mind. But there is one name that deserves to be amongst this pantheon, but rarely is- a man born just a couple of miles from where I’m writing now, in the inner-city suburb of North Melbourne.

Alan Villiers was born on 23 September 1903, second of six children to Anastasia and Leon Villiers, a tram driver, trade-union organiser and poet. Jack, as his family called him, (his middle name was John) went to Essendon High School, and then in 1919 a sailing school conducted by the Melbourne Ancient Mariners’ Club, who were known for helping the families of those working at sea and raising funds for the war effort.

Following a sailing injury (which is hard to gather details on), Villiers settled in Hobart in 1923, learning typing and shorthand and working for the Mercury. In 1923-24 he sailed to the Antarctic in the Norwegian whaler Sir James Clark Ross; his book, Whaling in the Frozen South (1925), was based on his articles for the Mercury. he also wrote a historical account of the port of Hobart.

In 1928 and 1929 Villiers had sailed in the annual ‘grain race’ from South Australia to England, resulting in the books Falmouth for Orders (1928) and By Way of Cape Horn (1930), and the film Windjammer (1930). There followed many projects requiring his formidable skills of seamanship, command and organisation: sailing with the Parma in the 1932 and 1933 grain races; as proprietor of the sail-training vessel, Joseph Conrad, in 1934-36; training as a pilot, 1937-38;

In the late 1930s Villiers began a survey to record the Arabian sailing methods of various types of Arab dhows – baggalas, booms, badans, belems, betils, bedeni, ghanjahs, jalboots, sambuks and zarooks – as they sailed on trading voyages through the Persian and Oman Gulfs, the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea as far south as Tanzania in East Africa. Villiers believed he was seeing the last days of sail and wanted to record the vessels before they disappeared.

It was out of this Arabian adventure that perhaps his most evocative book was born.

The first American Edition Published by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940

The premiss at the core of the book is simple.

Villiers gains a passage on a Kuwaiti boom (a medium-sized deep-sea dhow) called “The Triumph of Righteousness” and sails from Aden to the Swahili coast and then home to Kuwait between December 1938 to June 1939. Built by master shipwrights, stately booms like the Triumph were the typical cargo vessels of Kuwaiti seafarers. The story told with a very linear timeframe. Modern English teachers or contemporary film makers would despair at the rigid chronology, however the way he gently removes himself from the frenetic action and observes the sailing methods, personalities, religions and cultures of this majestic, squalid, overcrowded, and intriguing lateen rigged craft, kept me turning pages well into the night.

Much of the writing has to be seen through the lens of pre-war sensibilities but there is none of the ostentatious racism that you find with Joshua Slocum and Alain Gerbault. Villiers puts up with the trying conditions (including a blow to the head from a rigging failure which leaves him incapacitated and partially blind for a month) with no self pity or complaint. He judges his fellow crew and passengers not on their status, wealth or appearance, but on their abilities and attitudes. He’s not affraid to critisice but only when criticism is due. Take this moving passage about the death of one of the women travelling in the bowels of the “Triumph” . (“Nejdi” is the Captain of the boom)

Villiers manages to convey so much in these four short pages. His outrage at conditions the women on the boom were forced to endure. The iniquity of the roles that muslim women were (and in some parts of the world, still are) forced to play, the smells and textures of the great cabin, and the flippancy with which the sailors address matters of life and death. Its rarely heavy handed, and always judgementally restrained, but in the end his impressions are so much more powerful, as the come not from a pulpit, but the fastidious descriptions of the world in which he was immersed.

Supporting Villiers prolific story telling there is a substantial record of his extraordinary photography. Most of it seems to be held by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. You can a rich half an hour browsing the collection here. We take so much for granted nowadays with light, automatic, high-definition cameras in every pocket and handbag in the developed world, but in viewing these images remeber that Villiers like that another great adventurer Frank Hurley was dealing with unwieldy equipment, erratic and slow reacting film stocks, and the vagaries of silver halide development in climactic conditions that could make reliable chemistry a lottery. (click to enlarge)

Ostensibly, Villiers justifies his adventure by describing it as a voyage of factual discovery. Unearthing the details, histories and working methods of the myriad of working craft in the gulf of Arabia and its surrounding sea. Their differences are slightly masked by their one uniting feature, the lateen sail. And without being toodryly scientific about it, he does this well. However there seems to be little doubt as to the true purpose of the journey- The craving for adventure. Perhaps 85 years on, this is the point of connection to the current world, the reason I allow myself one more page when I should be turning out the light. It’s not impossible to find adventure in todays existence. We only have to look at Tom Robinson’s amazing feats to see that the potential for adventure is all around us.

“When I departed Peru 15 months ago perhaps it was not clear, even to myself, why I was rowing across the Pacific, but since then it has become well and truly clear. It wasn’t about breaking a record; it wasn’t about the final destination. Fame and glory can go the way of sympathy. They can all be damned. I went out into the Pacific chasing adventure, proper old-fashioned seat-of-the-pants adventure.”

But adventures of this sort nowadays seem to be based on extreme physical challenges. As isolated cultures and forgotten societies are infiltrated by thrill seekers wielding the tools of social media, finding truely original and enriching adventures seems harder and harder. I’m sure they are out there somewhere. And heaven forbid we ever stop trying!